See for yourself how Quartix works with our fully interactive real-time demo.

Andy Walters founded Quartix in 2001 with three colleagues. All four founders are still associated with the company, which now has more than 7,000 fleet clients, and operations in the UK, France and USA. Quartix has also carried out more than 110,000 installations for telematics-based insurance policies. Prior to Quartix, Andy held senior positions in technology and communications businesses within Schlumberger and Spectris.

In my last blog article, I looked at the introduction of vehicle tracking into a mobile workforce, focusing in particular on the impact on employment contracts and implementation issues.

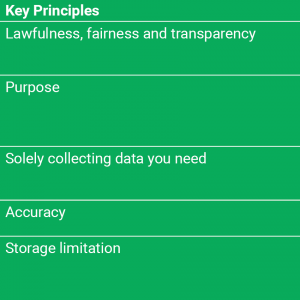

In this article, I will concentrate on the implications of vehicle monitoring with respect to the Data Protection Act and Article 8 of the Human Rights Act. A good guide to this is published by the Information Commissioner’s Office, or ICO. Part 3 of their guide specifically covers “Monitoring at work,” including vehicle tracking. It lists the following core principles:

- It will usually be intrusive to monitor your workers.

- Workers have legitimate expectations that they can keep their personal lives private and that they are also entitled to a degree of privacy in the work environment.

- If employers wish to monitor their workers, they should be clear about the purpose and be satisfied that the particular monitoring arrangement is justified by real benefits which will be delivered.

- Workers should be aware of the nature, extent and reasons for any monitoring unless (exceptionally) covert monitoring is justified.

- In any event, workers’ awareness will influence their expectations.

It is useful to start with the third of these principles. Can vehicle monitoring be justified by real benefits which will be delivered? The overwhelming answer from our customers is yes, but despite this, it remains essential to manage this telematics technology in a way which respects the rest of the core principles and the Acts themselves. Article 8 of the Human Rights Act, which states that “everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence” is also covered by these principles, and so what follows here is a short guide concerning the impact of both Acts on the use of vehicle telematics tracking:

Personal data. In the context of vehicle telematics tracking this is mainly the storage and processing of information related to places visited and routes driven by an employee in his or her own personal time. If the employee is allowed to use the vehicle for private purposes, he must, as a minimum, be aware of this practice and must have consented to it freely. The vehicle tracking system should preferably be set to maintain complete privacy for the driver’s personal time (see below).

‘Covert’ installations. The guide makes it clear that installing a monitoring telematics box without the employee’s knowledge will rarely be justified. It is also difficult to justify in management terms – as the user would be able to do nothing useful with the data. An example of this in our customer base concerned a worker and co-worker claiming 8 hours each at double time for a job carried out on a Sunday. The vehicle tracking system, which had been installed without their knowledge, showed that they had been present on site for just 2.5 hours. Unfortunately, the workers’ timesheets could not be challenged because they had been unaware of the presence of the vehicle tracking system, and the employer had to pay for 27 unwarranted hours of labour. Had the workers been aware of the vehicle tracking system they would not have filed a fraudulent timesheet in the first place and the discrepancy would not have arisen.

Maintaining worker privacy. One of the unique features of the Quartix vehicle tracking system is that privacy settings for personal time can be customized and maintained via our website or the driver’s mobile phone. The employer can set up standard working hours profiles for each vehicle (covering Monday to Friday, Saturday and Sunday), and the system will not record vehicle movements outside of these periods. The user can, however, override this using his or her mobile phone, by sending a coded text message. Similarly, bank holidays and annual vacation periods can be ignored by the vehicle tracking system simply by changing the configuration on the website. The telematics system still maintains the ability to locate the vehicle in the case of theft.

Access to data. It is important that workers are aware of what information is being recorded, and why. It is also important that they should have free access to the data stored and be allowed to challenge it. Some systems dispatch vehicle tracking reports by e-mail to the employer and can also dispatch the same reports directly to the user of the vehicle – so that he or she is aware of the data at the same time as the HR department.

Control of data. The provisions of the Data Protection Act apply to the control, storage and processing of personal data recorded by a vehicle tracking system, although it would be impossible to cover these in enough depth in this article. Breaches of the Data Protection Act fall under the purview of the ICO, as do the subsequent investigations. For breaches that are deemed serious, heavy penalties can apply. It is recommended that use of the vehicle tracking system is placed under the control and management of those responsible for compliance with the Act within the organisation.

In my next post, I will bring together the various topics covered in the first three articles by presenting a case study of the implementation of vehicle tracking in a large fleet – looking at the financial benefits, implementation issues and management of the telematics system.